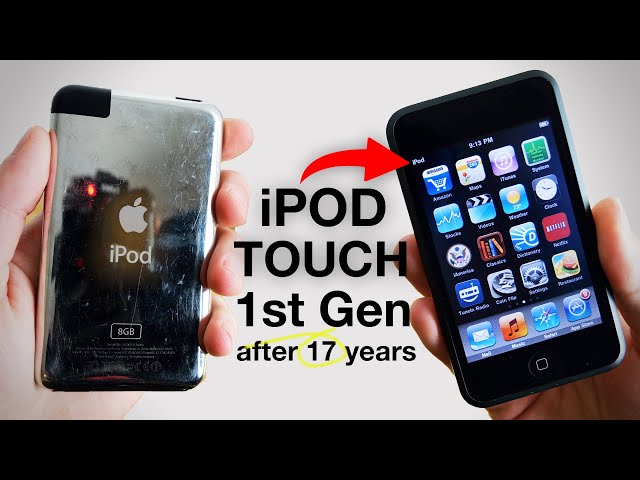

I still have my original iPod Touch in a drawer somewhere.

It’s scratched to hell. The stainless steel back looks like someone took sandpaper to it, and the battery holds a charge for maybe four minutes. But I keep it. There’s something about that first generation of hardware—the S5L8900 SoC, the 128MB of RAM (which seemed huge at the time), and that primitive, icon-grid interface—that feels historically heavy.

For the last decade, preserving this stuff has been a nightmare. If the hardware dies, the software dies with it. Or at least, that was the case until recently.

I spent last weekend messing around with the latest QEMU forks floating around the dev community, specifically the ones targeting the S5L8900 chipset. Well, the black box is finally cracking open. And it is messy, glorious, and surprisingly functional.

Why is this so hard?

You’d think emulating a device from 2007 would be trivial on a modern machine. But raw power isn’t the problem. Documentation is. Apple never released datasheets for the Samsung S5L8900. Everything we know comes from reverse engineering, staring at bootrom dumps, and trial-and-error that would drive a normal person insane.

The recent breakthroughs have changed the game. We aren’t just booting the kernel anymore; we’re getting into userspace. We’re seeing the SpringBoard.

The Setup: Not for the faint of heart

I decided to build the environment on my Linux rig (Ubuntu 24.04, kernel 6.8) because doing this on macOS is currently a pain with the entitlement issues. And the dependency list was long enough to make me question my life choices.

Here’s a tip I learned the hard way: Don’t use the default GCC version provided by Ubuntu. It threw a bunch of warnings about strict aliasing that eventually caused the emulated MMU to behave erratically. I switched to a toolchain specifically built for ARMv6 bare-metal development, and the stability improved instantly.

The command line to launch this thing is a monster. It looks something like:

./qemu-system-arm -M ipodtouch1g -cpu arm1176 -m 128 -kernel xnu-kernel ...

The “It Works!” Moment

The first three times I ran it, it crashed immediately. But I tweaked the memory mapping for the framebuffer, and this time, scrolling text. A lot of it. The XNU kernel initializing, drivers loading, the BSD subsystem waking up. It’s incredibly satisfying to watch 2007-era verbose logs fly by on a 2026 terminal.

Then, the screen flickered. It wasn’t perfect, but there it was. The “Slide to Unlock” bar.

I tried to slide it. Nothing happened. Right. Multitouch emulation. Mapping a mouse pointer to a multitouch controller is… weird. But I clicked, dragged, and the knob slid across. The distinct click sound played (audio is working! sort of!).

I was in.

The Reality of Emulation in 2026

Let’s be real: this isn’t ready for general users. I tried running the mobile Safari browser, but the rendering engine from 2007 had a panic attack trying to process modern TLS certificates. The web has moved on, and iPhoneOS 1.0 has not.

However, the stock apps? They work. Calculator, Stocks (RIP), Notes. The skeuomorphism hits you like a truck. It’s a time capsule.

A Technical Gotcha: The Timer

Here’s the specific issue that tripped me up: The system timer emulation is drift-prone.

I had to pin the QEMU process to a specific core on my host CPU (taskset -c 2) to give it dedicated resources. Once I did that, the UI smoothed out, and the lockups stopped. If you’re trying this, give the emulator its own core.

Why bother?

It’s about verification. We are losing the history of mobile computing. Emulation is the only lifeboat. By documenting the hardware behavior in code, we save the machine itself, not just the software.

Plus, there is a very specific, nerdy joy in seeing that boot logo on a 4K monitor. It feels like getting away with something.

What’s Next?

The community is currently banging its head against the GPU. The PowerVR MBX Lite inside these chips is a proprietary mess. Right now, everything is software rendered, which explains the 15 FPS. If someone manages to translate the MBX commands to Vulkan or OpenGL, we could see full speed, hardware-accelerated UI.

I wouldn’t hold my breath for that happening before 2027, though. The documentation for those old PowerVR chips is even scarcer than the Samsung SoCs.

For now, I’m just happy I can slide to unlock. Even if it takes a few tries.