The Surprising Second Act for a Discontinued Icon

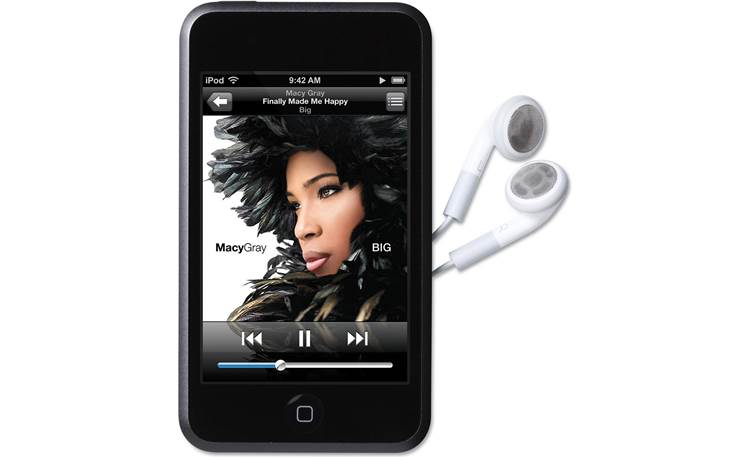

In the ever-accelerating world of technology, devices are often forgotten as soon as their successors are announced. The iPod Touch, once a revolutionary gateway to the world of apps and multi-touch for those without an iPhone, was officially discontinued by Apple in 2022, marking the end of an era. While the physical hardware may be fading into obsolescence, a dedicated community of developers, security researchers, and hobbyists is giving this iconic device a remarkable digital afterlife. Recent breakthroughs in emulation are allowing the original 2007 iPod Touch 1G and its groundbreaking software, iPhoneOS 1.0, to run on modern computers. This isn’t just a nostalgic trip down memory lane; it’s a significant technical achievement that opens new doors for digital preservation, security analysis, and understanding the very foundations of the modern Apple ecosystem.

This deep dive explores the monumental challenge of emulating Apple’s early, closed-source hardware, the technical wizardry required to make it happen, and the profound implications of this work. From preserving a pivotal piece of computing history to offering new insights into iOS security, the virtual resurrection of the iPod Touch is one of the most fascinating developments in the retro-tech landscape, providing a stark contrast to the latest Apple Vision Pro news and the ever-expanding universe of Apple products.

Section 1: The Anatomy of a “Forbidden” Emulation

Emulating a device like the first-generation iPod Touch is fundamentally different and vastly more complex than emulating a classic Nintendo or Sega console. The difficulty stems from Apple’s long-standing “walled garden” philosophy, which extends from the App Store all the way down to the hardware’s boot process. Successfully virtualizing the iPod Touch requires overcoming several layers of hardware and software security that were designed specifically to prevent this kind of reverse engineering. This effort provides a unique lens through which to view current Apple privacy news and the company’s historical commitment to a locked-down platform.

The Hardware Hurdle: Replicating Apple’s Custom Silicon

At the heart of the first iPod Touch (and the original iPhone) was the Samsung S5L8900 system-on-a-chip (SoC). This chip contained a 32-bit ARMv6-based CPU (the ARM 1176JZF-S) clocked at 412 MHz and a PowerVR MBX Lite GPU. While QEMU (Quick EMUlator) is a powerful and versatile open-source tool capable of emulating many CPU architectures, including ARM, the challenge lies in the peripherals. Emulating the CPU is just the first step. A successful project must also accurately replicate:

- The GPU: The PowerVR MBX Lite was responsible for rendering the revolutionary “skeuomorphic” interface of iPhoneOS 1.0. Without proper GPU emulation, the user interface would be a non-functional, garbled mess.

- Memory Controller and Peripherals: Accurately simulating how the SoC manages RAM, NAND storage, and communicates with components like the display controller, touch input processor, and Wi-Fi chip is critical for the operating system to even boot.

- Interrupt Controllers: These are essential for managing how hardware components signal the CPU, a fundamental aspect of any modern computing device.

This intricate hardware puzzle is why, for years, stable emulation of early iOS devices seemed impossible. Unlike gaming consoles with well-documented hardware, Apple’s custom silicon was a black box, requiring painstaking reverse engineering and analysis.

The Software Fortress: Decrypting the Boot Chain

Even with perfectly emulated hardware, you can’t simply load iPhoneOS like a disk image. Apple devices employ a secure boot chain, where each stage of the boot process cryptographically verifies the next. This chain typically looks like this:

- Boot ROM: The first piece of code that runs, embedded in the SoC silicon itself. It’s immutable and establishes the hardware “root of trust.”

- LLB (Low-Level Bootloader): Loaded and verified by the Boot ROM.

- iBoot: The main bootloader, responsible for verifying and loading the kernel.

- Kernel: The core of the operating system.

Each of these stages is encrypted with keys that are specific to the device. The jailbreaking community of the late 2000s and early 2010s spent countless hours finding exploits in this chain to run custom code. Emulation projects leverage this historical research, using known vulnerabilities and decrypted firmware images to bypass the security checks within the virtualized environment. This intersection of hacking and preservation is a core theme in the ongoing story of iOS security news.

Section 2: A Technical Deep Dive into the Emulation Process

Bringing an iPod Touch 1G to life in QEMU is a masterclass in low-level systems engineering. It involves meticulously building a virtual platform that mirrors the physical device’s behavior, allowing the original, unmodified iPhoneOS 1.0 firmware to run, blissfully unaware that it’s not on native hardware.

Step 1: Defining the Virtual Machine in QEMU

The process begins by defining a new “machine type” within QEMU. This involves writing C code that tells QEMU how to construct the virtual iPod Touch. This definition includes:

- CPU Model: Specifying the exact ARM1176JZF-S core.

- Memory Map: Allocating virtual RAM and defining the memory addresses for all the hardware peripherals (e.g., where the display controller’s registers are, where the NAND controller lives, etc.). This map must be identical to the real hardware.

- Peripheral Emulation: This is the most labor-intensive part. Developers must write “device models” for each critical component. For example, the display controller model needs to interpret commands written to its virtual memory addresses and translate them into an actual image that can be displayed in a window on the host computer. The touch input model must translate mouse clicks from the host into touch events that iPhoneOS can understand.

Step 2: Loading and Executing the Bootloaders

Once the virtual hardware is defined, the next challenge is to kickstart the secure boot chain. Researchers use decrypted firmware files, often obtained from the jailbreaking community archives, to load the Boot ROM and subsequent bootloaders into the virtual machine’s memory. The emulator must be precise enough to handle the delicate handshake between these components. For instance, when iBoot attempts to initialize the display, the emulated display controller must respond exactly as the real hardware would. Any deviation would cause the bootloader to hang or crash, halting the entire process.

Case Study: Emulating the Framebuffer

A concrete example of the complexity involved is emulating the framebuffer—the area of memory that holds the pixel data for the screen.

- The virtual iBoot writes initialization commands to the emulated display controller’s memory-mapped registers.

- The QEMU device model for the display controller interprets these commands and sets up a virtual framebuffer in the host machine’s RAM.

- iBoot then begins writing pixel data (e.g., the initial Apple logo) into the framebuffer’s memory address.

- The QEMU device model continuously reads this virtual framebuffer and uses a library like SDL or GTK to render it to a window on the user’s desktop.

- When the user clicks on this window, QEMU translates the coordinates into a touch event and passes it to the emulated touch controller, which then signals the virtual CPU.

This intricate dance, repeated for every single hardware component, is what makes the final result—seeing the iconic “slide to unlock” screen appear—so impressive.

Section 3: Implications and Insights for the Modern Apple Ecosystem

While emulating a 15-year-old device might seem like a niche hobby, the success of these projects carries significant implications that resonate with today’s Apple ecosystem news. It’s more than just running old apps; it’s about understanding the past to better contextualize the present and future.

Digital Archeology and Software Preservation

iPhoneOS 1.0 was a watershed moment in computing. It defined the paradigm of the modern mobile operating system. However, as physical iPod Touch units fail, this pivotal software risks being lost to time. Emulation provides a sustainable way to preserve and study this software for future generations. Historians and researchers can interact with the OS, study its UI/UX innovations, and analyze its code in a way that watching videos or looking at screenshots never could. This preservation effort is a vital counterpoint to the relentless forward march of iOS updates news, ensuring the foundational versions are not forgotten.

A New Frontier for Security Research

The ability to run early iOS versions in a controlled, observable environment is a goldmine for security researchers. They can:

- Analyze Historical Vulnerabilities: Study the exploits that powered the first jailbreaks to understand the evolution of Apple’s security model.

- Dynamic Analysis: Use the emulator’s debugging tools to pause execution, inspect memory, and trace system calls in real-time, offering a level of insight that is incredibly difficult to achieve on physical hardware.

- Fuzzing and Vulnerability Discovery: Automate the process of feeding malformed data to the emulated OS to discover new, or long-forgotten, security flaws. This work directly informs modern iOS security practices by highlighting foundational architectural decisions.

This is especially relevant as we see the Apple ecosystem expand into new categories with products like the Apple Watch and Vision Pro, which inherit much of their security architecture from iOS.

From Touch to Spatial: A Developmental Through-Line

Studying iPhoneOS 1.0 in an emulator provides a fascinating look at the DNA of Apple’s current software. The core principles of a fluid, touch-first interface, sandboxed applications, and tight hardware-software integration were all born here. Seeing these fundamentals in their nascent form provides a deeper appreciation for the complexity of modern operating systems like visionOS. The journey from the simple tap-and-swipe of an iPod Touch to the gesture and eye-tracking controls of the Vision Pro is a direct evolutionary path. The latest Apple Vision Pro news about its interface can be traced back to the groundbreaking work done on this first-generation OS.

Section 4: Best Practices, Pitfalls, and Getting Involved

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/ios-26-c16137dd93fc404aa00bba8f06e1430a.jpg)

For those inspired by this fusion of retro-tech and modern software engineering, diving into the world of iOS emulation can be a rewarding, albeit challenging, endeavor. Here are some practical considerations.

Tips and Best Practices

- Start with Documentation: The key to success is building on the work of others. Thoroughly read the documentation and blog posts of existing projects to understand their architecture and the challenges they overcame.

- Master the Tools: A strong understanding of QEMU, a C programming language, and ARM assembly is invaluable. Familiarity with debugging tools like GDB is also essential for troubleshooting when the virtual machine inevitably crashes.

- Legal and Ethical Considerations: Be aware that while the emulation software itself is legal, using and distributing Apple’s copyrighted firmware files exists in a legal gray area. Always use firmware extracted from a device you personally own.

Common Pitfalls to Avoid

- Underestimating Complexity: Don’t expect a plug-and-play experience. Emulating a closed system is a marathon, not a sprint. Many features, like sound, Wi-Fi, or full-speed graphics acceleration, may be unimplemented or buggy.

- Hardware Inaccuracies: The most common source of failure is a subtle inaccuracy in the hardware emulation. A single incorrect memory address or a mis-timed interrupt can lead to inexplicable crashes that are difficult to debug.

- Performance Bottlenecks: Emulating a system-on-a-chip is computationally expensive. Even though the original iPod Touch was slow by today’s standards, emulating it requires a powerful host machine, especially for achieving near-real-time performance.

The rise of these projects is a testament to the power of open-source collaboration and a shared passion for technological history. It’s a niche but important corner of the tech world, blending nostalgia with cutting-edge reverse engineering, and it provides a unique perspective on the broader trends in iPod news and the legacy of Apple’s most iconic products.

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy of the iPod Touch

The successful emulation of the first-generation iPod Touch and iPhoneOS 1.0 is more than just a technical stunt; it is a celebration of a device that changed the world. It ensures that a critical piece of digital history remains accessible and interactive, providing invaluable lessons in software design, hardware engineering, and security. This work serves as a powerful reminder that even as Apple pushes forward with groundbreaking products and the latest Apple health news or Apple AR news, there is immense value in looking back at the foundational technologies that made it all possible. The digital resurrection of the iPod Touch proves that while hardware may be discontinued, a truly revolutionary product never really dies—it simply finds new life in the code of a passionate community.