The Ghost in the Machine: Unlocking Apple’s Past Through Emulation

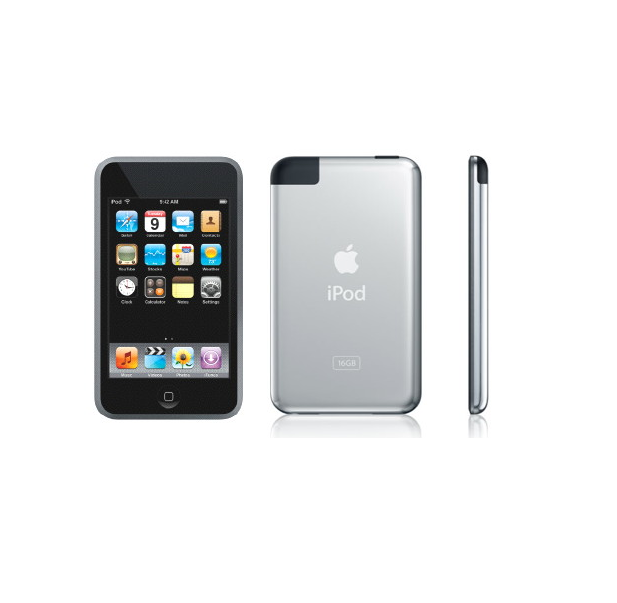

In the fast-paced world of technology, where the latest Apple Vision Pro news dominates headlines and annual iOS updates news renders older systems obsolete, it’s easy to forget the devices that started it all. The first-generation iPod Touch, launched in 2007, was a revelation—a sleek slab of glass and metal that offered the core experience of the original iPhone without the cellular contract. It was the gateway to multi-touch, mobile Safari, and the nascent world of web apps. Today, these devices are relics, their software frozen in time. Yet, a dedicated community of developers and enthusiasts is breathing new life into this iconic hardware, not by polishing the aluminum, but by meticulously recreating it in the digital realm through emulation. This process of digital archeology is more than just a nostalgic trip; it’s a complex technical endeavor that offers profound insights into the evolution of the entire Apple ecosystem news, from the earliest iPods to the latest AirPods Max news.

This article delves into the fascinating and challenging world of emulating the first-generation iPod Touch and its groundbreaking operating system, iPhoneOS 1.0. We will explore the technical hurdles of recreating Apple’s famously closed hardware, the tools used to overcome them, and what this digital preservation effort teaches us about security, design, and the very DNA of modern computing. This journey from a simple media player to a sophisticated ecosystem of interconnected devices like the Apple Watch and HomePod mini began here, and by emulating its origins, we can better understand its trajectory.

The Herculean Task: Emulating Apple’s Early ARM Architecture

Emulating a device as iconic as the first iPod Touch is not as simple as running a vintage game on a modern PC. The fundamental challenge lies in Apple’s “walled garden” philosophy, which extends from the App Store all the way down to the silicon. Unlike the open architecture of early PCs, Apple’s hardware and software are tightly integrated and intentionally opaque, making the task of recreation a masterclass in reverse engineering.

Why It’s Not Just “Running an Old App”

The core of the iPod Touch 1G was the Samsung S5L8900 system-on-a-chip (SoC), an early ARM-based processor that was custom-designed for Apple. Emulation requires a tool like QEMU (Quick EMUlator) to translate the ARM instruction set of the iPod’s CPU into the x86 instructions that a modern Mac or PC can understand. This is the first major hurdle. However, a CPU does not exist in a vacuum. The SoC also contained a host of specialized hardware components—a PowerVR MBX Lite GPU, a multi-format codec for video, display controllers, and interfaces for NAND storage and Wi-Fi. For the operating system to function, the emulator must not only process CPU instructions but also convincingly pretend to be all of this peripheral hardware. If iPhoneOS asks to write a pixel to the screen buffer, the emulator must intercept that command and draw a pixel in a window on the host computer. This level of hardware simulation is monumentally complex and is a stark reminder of the intricate engineering that goes into even the earliest Apple devices.

The Software Hurdle: Deconstructing iPhoneOS 1.0

Even with a perfect hardware emulation, you still need the software. Getting a copy of iPhoneOS 1.0 is one thing, but making it boot on a virtual machine is another. Apple’s devices employ a secure boot chain to ensure that only signed, authentic Apple software can run. This process begins with a Boot ROM embedded in the silicon, which loads and verifies a bootloader (known as iBoot), which in turn verifies and loads the main operating system kernel. To successfully emulate the device, developers must reverse-engineer this entire process, understanding how the hardware and software cryptographically handshake. This early focus on a secure startup process is the ancestor of the robust security features we read about in modern iOS security news. It laid the foundation for technologies like the Secure Enclave and the stringent Apple privacy news policies that define the brand today. The simplicity of iPhoneOS 1.0, with its lack of an App Store, Siri, or advanced features, stands in sharp contrast to the feature-rich environment of today, but the seeds of Apple’s security-first mindset were already planted.

Tools of the Trade: A Digital Archeologist’s Kit

Successfully emulating the iPod Touch requires a specialized set of tools and a deep understanding of low-level systems. The open-source community, driven by a passion for preservation and technical curiosity, has been at the forefront of this effort, with QEMU serving as the cornerstone of the project.

QEMU: The Universal Translator

QEMU is the workhorse of the hardware emulation world. At its core, it is a dynamic translator that can execute machine code intended for one CPU on a completely different CPU. For the iPod Touch project, developers have taken the standard QEMU source code and heavily modified it. They’ve added support for the specific ARMv6 instruction set used by the S5L8900 SoC and, more importantly, begun the painstaking process of writing virtual models for the iPod’s unique hardware. This involves studying datasheets (when available), analyzing the disassembled iPhoneOS code to see how it interacts with the hardware, and a great deal of trial and error. For example, to get the display working, a developer must create a virtual display controller in QEMU that responds to the same memory addresses and commands as the real hardware, translating those commands into a visual output on the host machine.

Beyond the CPU: Emulating the Peripherals

Making iPhoneOS 1.0 boot to a command line is a major achievement, but making it usable requires emulating the peripherals that defined the user experience. The most critical of these is the multi-touch screen. Developers must create a virtual touchscreen that can pass simulated touch and gesture data to the virtual iPod. This is a fascinating challenge, as it requires understanding how the original hardware translated capacitive touch into X/Y coordinates and gestures like “pinch-to-zoom.” This work on fundamental input methods provides a unique perspective on the evolution of user interfaces, from this early multi-touch to the sophisticated hand-tracking and input methods discussed in Apple Pencil Vision Pro news. Similarly, emulating the audio controller is necessary to hear the classic “click” sounds of the UI or play music—a core feature that connects this project to the entire legacy of iPod news, from the iPod Classic news to the iPod Nano news. Each emulated component, from the Wi-Fi chip to the accelerometer, is a project in itself, highlighting the integrated nature of Apple’s product design.

Unlocking the Past: Insights and Implications

The successful emulation of an iPod Touch 1G is more than just a technical showcase; it is a powerful tool for preservation, research, and education. It provides a living, interactive museum exhibit of a pivotal moment in computing history and offers tangible insights into the principles that still guide Apple today.

A Window into Apple’s Design Philosophy

Running a virtual iPod Touch allows us to experience iPhoneOS 1.0 as it was meant to be used. We can see the origins of skeuomorphism in the yellow legal pad of the Notes app and the calculator that looked like a real calculator. We can appreciate the fluidity of inertial scrolling, a feature that felt like magic in 2007. This experience provides a direct line of sight into Apple’s early design philosophy: making technology intuitive by grounding it in real-world analogues. This foundation is still visible, albeit in a more abstract form, across the entire product line, from the simple setup of a HomePod to the intuitive interface of the Apple TV. This digital preservation effort is the closest thing we have to true iPod revival news, allowing a new generation to understand the device’s impact.

Preservation and Security Research

Hardware degrades. Batteries fail, screens crack, and NAND memory wears out. Without emulation, the experience of using these foundational devices would eventually be lost forever. Emulation preserves this crucial chapter of digital history in a format that is accessible and durable. Furthermore, it provides an invaluable sandbox for security researchers. By running the OS in a controlled virtual environment, researchers can probe for early vulnerabilities, understand how exploits worked, and trace the evolution of Apple’s security mitigations over 15+ years of iOS development. This historical context is vital for understanding the current landscape of mobile security and appreciating the advancements in features like Apple’s BlastDoor and Lockdown Mode. It also informs our understanding of the ongoing cat-and-mouse game between platform holders and security threats, a topic frequently covered in Apple privacy news.

The Foundation for the Modern Apple Ecosystem

The iPod Touch was the Trojan horse for the iOS ecosystem. It was the training wheels for the App Store, introducing millions of users to a touch-based OS before they ever owned an iPhone. Emulating it reminds us how a single, focused product can lay the groundwork for a sprawling empire of interconnected devices and services. The core principles of a portable, ARM-based computer with a touch-first interface are now present in everything from the iPad to the Apple Watch. The seamless connectivity we expect from our AirPods Pro and the smart home integration of a HomePod mini all trace their lineage back to the simple Wi-Fi connection on that first iPod Touch. Even cutting-edge concepts in Apple AR news and the spatial computing of the Vision Pro are built upon the user interface paradigms established by this device.

From iPod Touch to Vision Pro: The Emulation Frontier

The work being done to emulate the first iPod Touch is part of a larger movement to preserve and understand our digital heritage. As technology accelerates, the challenges and importance of this work will only grow.

Pros and Cons of Emulation Efforts

The primary benefit of emulation is preservation. It democratizes access to historical technology, allowing anyone with a computer to experience a piece of computing history. It’s a powerful educational tool and an essential platform for security research. However, it’s not without its challenges. The process is technically demanding and relies on the passion of a small community of volunteer developers. Furthermore, it exists in a legal gray area. Emulation itself is legal, but it often requires dumping firmware and software from original hardware, which can violate user agreements and copyright law. This tension between preservation and intellectual property rights is a constant consideration for the community.

What’s Next for Retro Apple Emulation?

As the iPod Touch 1G emulation project matures, the community will likely set its sights on more complex targets. Emulating the first-generation iPad, with its larger screen and slightly more advanced A4 chip, is a logical next step. Other fascinating targets could include the first Apple TV (which ran a modified version of Mac OS X) or even an early-generation Apple Watch. However, the difficulty scales exponentially. The custom silicon in modern devices, like the R1 chip in the Apple Vision Pro, which is dedicated to processing sensor input with incredibly low latency, would be nearly impossible to emulate accurately with current technology. This highlights how far Apple’s custom engineering has come, making these emulation projects a race against increasing complexity and a tribute to the engineering of their time.

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy of a Pocket Revolution

The effort to emulate the first-generation iPod Touch is a testament to the device’s enduring impact. It is a complex and deeply technical pursuit that goes far beyond simple nostalgia. By digitally resurrecting this iconic piece of hardware, developers and researchers are preserving a critical piece of technological history, providing a sandbox for security analysis, and offering a unique lens through which to view the entire evolution of Apple. From the simple tap-and-swipe of iPhoneOS 1.0 to the intricate spatial computing of the Vision Pro, the journey of the last two decades is staggering. These emulation projects serve as a vital reminder that to understand where we are going, we must first understand—and preserve—where we began. The ghost in this virtual machine tells the story of how a music player in your pocket changed the world forever.